Introduction and Background

This TLRI project is part of a larger programme of research referred to as the Data, Knowledge, Action project. The Data, Knowledge, Action programme of research focuses on the development and use of innovative and authentic data systems to help early childhood teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand examine young children’s curriculum experiences and strengthen their teaching practice. To date the programme comprises of: a) a pilot study undertaken in 2017 to develop and trial innovative and authentic data systems to investigate children’s experiences of curriculum; b) a 18-month project funded by the Teacher Led Innovation Fund (TLIF) involving teacher-led inquiries into children’s experiences (July 2018 – December 2019; and c) this Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) funded project exploring sustained shared thinking to deepen young children’s learning (January 2019 – June 2021).

The broader research programme is focused on investigating data-informed teaching in early learning and understanding the capacities, skills and dispositions required to use authentic, observation-based data effectively. The research programme is a partnership among a multi-university research team and Ruahine Kindergarten Association. The research has been guided by the premise that effective data can lead to knowledge which can lead to action for improved teacher practice, curriculum implementation and positive learning outcomes (cf. Earl & Timperley, 2008; Gunmer & Mandinach, 2015).

This TLRI project extended on our previous work to undertake a deeper and more focused investigation of teachers’ engagement in sustained shared thinking in their interactions with children. Sustained shared thinking (SST) was selected as a focus area because it is a pedagogical strategy strongly associated with high-quality early childhood education (Meade et al., 2012; Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2002; Siraj-Blatchford, 2010) and is an area of pedagogy in which new data tools and systems could be further explored.

The TLRI research project was designed as two exploratory case studies using mixed methods data sources to address the research questions and to obtain descriptive and rich data about the experiences, opportunities, challenges and outcomes associated with SST. This report begins with an overview of data-informed teaching followed by a review of sustained shared thinking. The research questions are then described followed by the research methods, key findings, and conclusions from this research. We note this research occurred during the period in which COVID-19 closed Aotearoa New Zealand’s borders and we entered a nation-wide lockdown followed by periods of restricted alert levels. Due to the strong engagement of the teams and timing of inquiry cycles, we were able to proceed with our research with minor modifications to the original plan. Where applicable, these changes are described in this report.

Data-Informed Teaching

Helen Timperley’s work in Aotearoa New Zealand schools has long shown that the effective use of data can be a powerful driver of teaching and learning – with the power to transform and improve teaching practice and strengthen learner outcomes (Earl & Timperley, 2008; Timperley, 2010; Timperley & Robinson, 2001). McLaughlin et al. (2020) define data in education as “information relevant for learning and teaching collected through a known process for a known purpose” (p. 4). Data-informed teaching occurs when teachers use a range of sources of information to inform decisions about teaching and learning. These sources are gathered intentionally and include both formal (i.e., more structured) and informal (i.e., less structured) sources of information. In early learning, different forms and systems of observation are particularly well suited to gathering information in authentic settings for teachers and children (cf. Podmore, 2006).

While data has the potential to be a powerful driver of quality teaching and learning, it also has the potential to be mis-used or cause harm. It is critically important that data systems are designed with integrity and clarity, and that they are used for the purposes intended. Teachers and leaders should be aware of the ethical responsibility for ensuring positive outcomes from assessment and evaluation and guarding against unintended or harmful outcomes (Snow & Van Hemel, 2008). Moreover, teachers need the capabilities, mindsets, systems, and supports to effectively and appropriately use data to inform assessment and evaluation (Bocala & Boudett, 2015; Datnow & Hubbard, 2015, 2016). A key aspect of this project was to explore the supports needed that can equip teachers to use data effectively, appropriately, and in ways that empower both teachers and learners (and whānau).

Sustained Shared Thinking

The term “sustained shared thinking” (SST) was coined within the Effective Pedagogy in Preschool Education (EPPE) longitudinal study in the UK, in which the effects of preschool education on a range of cognitive and social outcomes for a national sample of 3000 children were examined. This study was followed up with intensive case studies of twelve settings which were associated with positive outcomes for children (the Researching Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years (REPEY) project; Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2002). The REPEY project identified SST as a key pedagogical feature of high-quality early childhood settings.

This early work defined SST as:

an episode in which two or more individuals ‘work together’ in an intellectual way to solve a problem, clarify a concept, evaluate activities, extend a narrative etc. Both parties must contribute to the thinking and it must develop and extend thinking. (Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2002, 2003; Sylva et al., 2004)

The use of the term “thinking” in SST, as opposed to “language” was a deliberate choice intended to highlight the cognitive emphasis of SST interactions; however, the role of language and developing children’s language is viewed as equally important in SST (Siraj-Blatchford, 2009). SST involves both relational and intentional pedagogy and curricular content, taking place in the context of play-based and everyday interactions (Siraj-Blatchford, 2010). Further description explains that SST is most likely a one-to-one interaction (Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2002; Siraj-Blatchford, 2010; Meade et al., 2012; Sylva et al., 2004), usually between an adult and child (Siraj-Blatchford & Manni, 2008; Siraj-Blatchford, 2010) although also possible between peers (Siraj-Blatchford, 2010).

Meade et al. (2013), in examining effective pedagogy in Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood settings, defined it as “’extra talk’ beyond the level of instruction that deepens children’s thinking” (p.8) and stressed the reciprocity of SST interchanges. Previous research has shown low levels of SST in early childhood contexts (Meade et al., 2012; Siraj-Blatchford et al., 2002,2003) with SST making up only a small proportion of teacher-child interactions. The complexity of SST may make it difficult to use regularly and effectively in the context of busy early learning settings. Nonetheless, within the exploration strand of Te Whāriki, the importance of kaiako encouraging sustained shared thinking is specifically noted.

Research Questions

This TLRI project sought to use a range of data tools to identify the characteristics of SST and the frequency with which SST is used to promote children’s learning. We also sought to explore the potential of data-informed teaching to extend or increase the use of SST to enhance children’s learning. Because SST focuses on both thinking and language, the Te Whāriki strands of communication and exploration were initially selected as focus areas. However, as noted by Meade et al. (2012) and Siraj et al. (2015), children’s developing social-emotional capabilities can also be supported through SST. This became evident in our project, as a strong focus on the wellbeing, belonging, and contribution strands of learning also emerged as key areas of focus for the participating teams following the COVID-19 lockdown period. Our fourth research question was revised to show this expanded focus.

The research was guided by the following research questions:

- How are children experiencing periods of sustained shared thinking with teachers in our kindergartens?

- How might teachers make sense of and use data about the nature of sustained shared thinking between teachers and children?

- What changes occur in sustained shared thinking between teachers and children when using data-informed teaching?

- How do changes in sustained shared thinking between teachers and children promote children’s progress across the curriculum learning outcomes?

Research Methods

Research Design

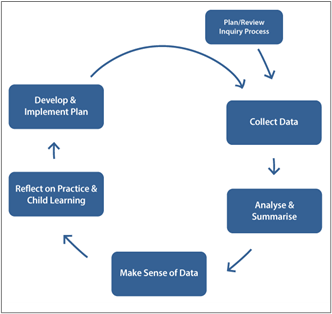

The study was conducted through exploratory case studies focusing on the experiences of teachers and children within two kindergarten settings. We employed a range of data collection and analysis tools to gather quantitative and qualitative research evidence. Each setting was supported to engage in successive cycles of data-focused inquiry (see Figure 1) using the planned data tools to examine SST. On-going inquiries were supported by the project teacher-researcher and critical friends. Throughout the inquiry cycles, we held a series of team and cross-team meetings with kindergarten teams to discuss and make sense of the data from their individual settings and form action plans for data-informed teaching.

In addition to the ongoing data collection conducted as part of the inquiry cycles, information about teachers’ perspectives of data and SST were gathered pre-post using focus groups and a project developed questionnaire. Details of data tools are described in the Data Collection and Analysis section below.